Seeing in the Dark: Dark Vessel Detection in Maritime Security

- Oliver Stringer-Jakins

- Apr 3, 2021

- 9 min read

[DISCLAIMER: The author of this article is a researcher for an ocean economy consultancy firm that leads in counter-IUUF projects around the world. The firm is also formally associated with OceanMind and Global Fishing Watch. However, they are not associated with ICEYE, Sea Shepherd, Oceana, Netflix, Konsberg Satellite Company, or any other organisation mentioned in this article. Lastly, this article was not paid for by any group, nor does it represent the views of any specific organisation. Sources can be provided upon request.]

Addressing the Problem of Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported Fishing (IUUF)

The recent Netflix documentary, Seaspiracy, dives into the harrowing side of industrial fishing practices. Whilst criticised for its macabre view of the fishing industry – a view that is generally justified when viewed next to the horrific scenes of whaling, shark finning, and bycatch – the documentary does touch on some very relevant points about IUUF.

Illegal fishing is a serious problem. Unsustainable practices are causing fish stocks to plummet in parts of the world where billions rely on fish for livelihoods and food. In addition, coral reefs, the global forests of the seabed, have a close relationship with fish to provide shelter and biodiversity, in exchange for the ammonium that fish excrete through their gills that is essential for coral growth. The aggressive loss to fish populations in areas of marine biodiversity is damaging this delicate symbiotic balance.

Seaspiracy also correctly highlighted the use of human trafficking in illegal fishing fleets. The documentary showed interviews of Thai fisherman who had been at sea for years as slaves. Likewise, the documentary featured Steve Trent of the Environmental Justice Foundation, who claimed that approximately 51,000 boats fishing under the Thai flag have directly contributed to forced labour.

Bradley Soule, Director of Intelligence from OceanMind, said in a recent Seeker documentary on using AI to track illegal fishing from space: “if you’re willing to break the rules for fisheries, you’re probably also willing to break the rules and abuse your crew, by forcibly keeping them on board the vessel which they can’t leave because it’s out at sea”.

Without a doubt, there is corruption and state-sponsorship of IUUF in places such as Japan and China. The taboo issue of whaling or shark finning is not to be avoided here. Luis Kutner's 1978 article: The Genocide of Whales: A Crime Against Humanity, set the international agenda of pursuing a global whaling ban. Four years later, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) established a ban on commercial whaling. However, as Seaspiracy pointed out, Japan withdrew from the IWC in 2018, and Norway and Iceland are still actively engaged in whaling.

IUUF in South-East Asia

Where Seaspiracy engaged in an attack on the idea of sustainable fishing as an impossibility, it missed the point that many fishing nations lack the resources to counter both corruption and IUUF.

Yet, governments in South-East Asia like Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines are pouring resources into combatting IUUF in their waters.

In the Western Pacific and the South China Sea, the issue of foreign encroachment is a major problem for this melee of maritime borders. Some estimates assess that only 50% of all fish caught in Malaysia’s national waters makes it to the local market at a loss to Malaysia of almost USD $1.5 billion per year. Likewise, Indonesia’s Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF) estimate that illegal fishing costs the country over USD $3 billion annually.

IUUF also proliferates related criminal activity to support it: document forgery; human trafficking; smuggling; money laundering; drug and firearms trafficking are amongst these related illicit activities. For example, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the South-East Asian methamphetamine trade originates in Myanmar and uses overland and maritime trafficking routes through Thailand and Malaysia... routes also used by IUUF vessels.

Diving deeper, illegal fishing vessels are entering foreign oceans with automatic identification (AIS) or vessel monitoring systems (VMS) either switched off or not installed. This essentially allows fishing vessels to slip into the dark, obscuring them from enforcement authorities such as the coast guard, navy or designated task forces.

In a report from Oceana in 2018, analyst Lacey Malarky and her team used AIS collected by Global Fishing Watch to track a Panamanian ship called Tiuna on the western boundary of the Galapagos Marine Reserve, one of the world’s most biodiverse regions. In October 2014, the vessel went dark for 15 days before it began transmitted again on the reserves eastern border.

Likewise, over 2015 and 2016, an Australian commercial fishing vessel called the Corinthian Bay, appeared to enter a no-fish marine reserve south of the Indian Ocean on ten separate occasions. According to the AIS data, the vessel went dark on entry into the reserve and turned on its AIS once it had exited. Despite the allegations, the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) stated the intentional disabling of the Corinthian Bay’s AIS revealed no suspicious activity.

Seeing in the Dark

In 2019, Finnish space start-up ICEYE launched Dark Vessel Detection, which uses a space-based synthetic aperture radar (SAR) system to scan the ocean looking for vessels operating illegally. This will enable users – governments, NGOs, navies, and coast guards – to access both location information and radar satellite imagery of illegal maritime vessels, even if they have their AIS turned off.

This is a ground-breaking system for maritime domain awareness (MDA) and leads a new fight against illegal activities in the ocean territories of nations. Additionally, if combined with AIS, ICEYE SAR can provide real-time, high-res images of suspect vessels larger than 10m, even in cloudy weather conditions.

Click the picture below to go to ICEYE's interactive demo:

Why is this system so important?

Take Indonesia, for instance. Indonesia is the largest archipelago nation in the world. On a map, it stretches to 5,100 km from east to west and consists of 17,508 islands. This essentially makes Indonesia a maritime labyrinth as wide as China, starting in the Indian Ocean and ending off the north-west tip of Queensland, Australia.

Indonesia’s ocean territory and its respective economic resources are defined by everything within 200 nautical miles of its 54,720km coastline. This is known as an exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and for Indonesia, it is enormous. According to the Indonesian Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, its EEZ is around 6.4 million km², 77% larger than its total land area and twice the size of India. It is therefore a monumental task to accurately police its maritime space, which threatens a marine ecosystem that accounts for around 27.2% of all flora and fauna species in the world.

Many vessels operating in Indonesian waters have either disabled their AIS or do not have one fitted in the first place, as much of Indonesia’s fishing fleet is artisanal and do not meet the size requirement for fitting AIS. Therefore, systems such as ICEYE SAR could aid the fight against IUUF as a major threat to maritime security in areas such as South-East Asia.

Dark Vessel Detection in Maritime Security

ICEYE’s Dark Vessel Detection system also has utility in maritime security. In collaboration with Konsberg Satellite Company, five images were taken between 21 April 2020 and 25 April 2020 around the Horn of Africa where Iranian vessels were operating in relatively high density. Additionally, the SAR data was matched with AIS, and showed 16 of the SAR vessel detections matched Iranian fishing vessels that were equipped with AIS. However, there was also an additional 44 detections that matched the profile and behaviour of an Iranian fishing vessel but did not match any known AIS signals.

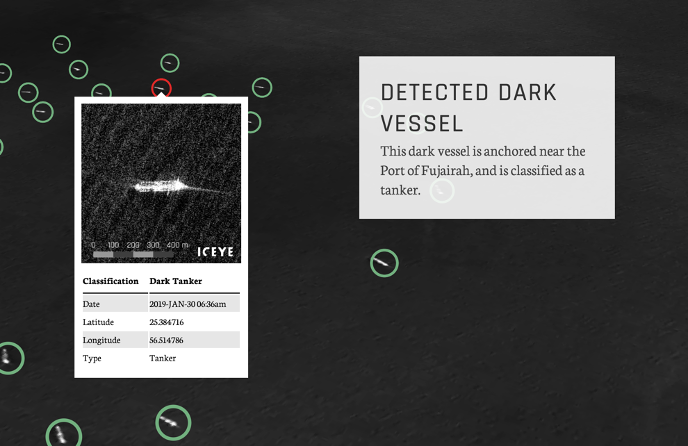

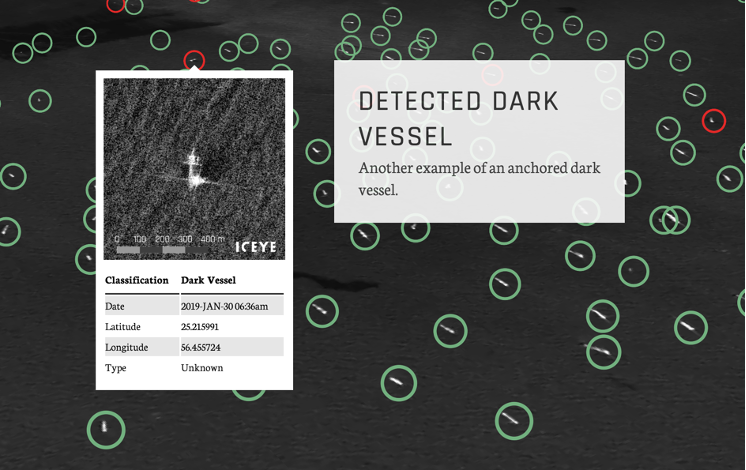

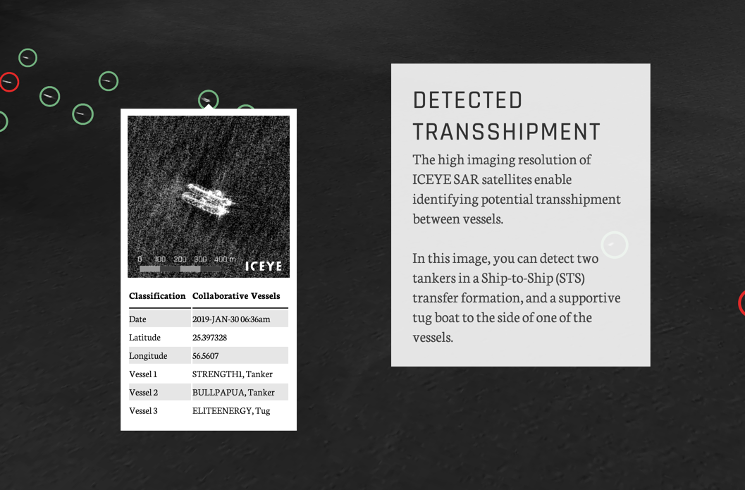

Another case study is in the Gulf of Oman. As pointed out by Ross Davies in his article for Ship Technology, the waterway was the centre of headlines in June 2019 after Iran was suspected to have attacked two oil tankers with limpet mines. In ICEYEs demo (below), dark vessels are shown to be moored near the UAE port of Fujairah. However, upon closer inspection of high-res images from ICEYE’s SAR satellites, it is instead two tankers hugged together in what appears to be an illegal at-sea transhipment.

Below is a slide show of the Gulf of Oman case study:

Transhipments are considered to be one of the major problems in IUUF as it is often used as a platform to avoid port controls and maximise profits. It allows fishers to avoid regulations, leading to overfishing and the catch of endangered fish species, but also has implications for environmental damage as transhipments are sometimes used to refuel or transfer waste.

Artificial Intelligence in the Fight against Illegal Fishing

There are other new technologies that are aiding maritime enforcement agencies to track illegal fishing. OceanMind, a UK-based non-profit organisation that empowers enforcement and compliance to protect the world’s fisheries, use a variety of technologies include remote sensing, Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence to track information on thousands of fishing vessels around the world.

OceanMind was aware of the STS-50, a fugitive fishing vessel that had stolen millions of fish in foreign waters over the years. The vessel was known in most areas of the world, ranging from the coasts of Africa, the Indian, Atlantic, and Pacific Oceans. To escape capture, the vessel had swapped names, flags, crew and homeports to create a “rotating cast of identities” and lied to port authorities by creating false documents about their catch and export.

Originally from Japan, it had changed names from the Andrey Dolgov, the Sea Breeze, and the Ayda. It evaded authorities for years, thought to have looted up to $50-million worth of fish. The captain was also a “master of escape”, and had evaded physical catch by naval authorities three times.

Working with INTERPOL and the Indonesian Presidential Task Force, OceanMind provided data that tracked the STS-50 to the Port of Mabuto, the capital of Mozambique. The ship's operator had not strictly switched off its AIS tracker, allowing it to blend in with background sea traffic.

OceanMind performed a forensic analysis of its tracking data to locate the STS-50 and notified the Indonesian Navy, which promptly pursued and arrested the fugitive vessel on April 6, 2018.

The catch held a symbolic presence for counter-IUUF groups. Firstly, it proved when efficiently used, technology provides a significant edge in the fight against illegal fishing. Secondly, it shows that illegal fishing is a common enemy in the world, rallying INTERPOL, Indonesia, Madagascar, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), private naval enforcement and conservationist group Sea Shepard, and many others, in an international effort to combat this elusive ship.

Sustainability and the Future Threat of IUUF

Seaspiracy, whilst illuminating a largely hidden problem to the general public, drilled home that “sustainability” was impossible in the global commercial fishing industry. Furthermore, the documentary set some difficult goals posts in the debate, by claiming that the definition of “sustainability” is part of the problem and that the ultimate solution is to stop eating fish all together or eat less of it.

Taking this apart, there a couple points to tackle. Firstly, the interview with the representative of Oceana, a non-profit ocean conservation organisation, was allegedly taken out of context to say she or Oceana did not have a definition of sustainability. Oceana made a FAQ page for the documentary and made this statement:

“To be clear, she meant that it can be confusing for consumers who try to buy “sustainable” seafood, not that Oceana does not have a definition for sustainability. We do have a definition (below), and we also know that it is possible to successfully put in place science-based management of fisheries and to create more abundance. In other words, we can save the oceans and feed the world.

The former Oceana staffer featured in the film was a key leader in our campaigns against illegal fishing. She was asked a question about consumer seafood guides in the course of a two-hour interview, which was selectively edited.

The filmmakers could have interviewed the Oceana representative about her years of work with Oceana to stop illegal fishing. She could have told filmmakers about how she, Oceana and allies helped make the European Union’s fishing fleet more transparent and accountable. Or, how Oceana organized global insurers to cut a financial lifeline to illegal fishers.”

Sustainability is definable, and certainly possible. Oceana campaigns for science-based management of fisheries, which can increase biodiversity and replenish fish stocks. Oceana champion that fishing can be done sustainably, such that “habitats, fish stocks, and coastal communities thrive.”

A proven example is in Bangladesh. In 2019, the Bangladesh government issued a ban on the capture of Hilsa, the national fish of Bangladesh. Initially banned for 65-days, the ban has been repeated for multiple periods of time since to replenish its population. Overfishing is a serious problem in Bangladesh, attributed to both foreign encroachment, but also because it lacks significant enforcement capability.

Bangladesh also has a generational debt problem. Many fisherfolk struggle to create livelihoods and have to borrow from local businessmen and suppliers with high interest to buy equipment, as banks will not lend to them. They are then forced to overfish to meet their debt quotas and feed their families.

Bangladesh has also been hit hard by cyclones such as Cyclone Bulbul (2019) that displaced millions of people who rely on the coast and fishing for food and livelihoods. Yet, despite sensitivity to climate change and natural disasters, Bangladesh still recognises need to manage its fisheries sustainably.

Sustainability is about more than just replenishing fish stocks. It's about resource allocation for the billions who rely on fish. Eradicating fishing, or radically reducing it, is equally unsustainable.

Seaspiracy does some great things on a mainstream-media platform such as Netflix, in the same way that films like Cowspiracy, What the Health, and Game Changers do to illuminate the problems associated with global food sectors such as agriculture, aquaculture, fishing and meat consumption.

It is imperative that we do not throw the baby out with the bathwater and instead focus on combatting the illegal side of fishing, by enabling enforcement agencies, certification groups, conservationists, marine scientists and commercial fishers to use new technologies to redefine the fishing industry in a way that allows humanity to live in harmony with the oceans.

That is the Blue Economy, and that should be the future of fishing.

[DISCLAIMER: The author of this article is a researcher for an ocean economy consultancy firm that leads in counter-IUUF projects around the world. The firm is also formally associated with OceanMind and Global Fishing Watch. However, they are not associated with ICEYE, Sea Shepherd, Oceana, Netflix, Konsberg Satellite Company, or any other organisation mentioned in this article. Lastly, this article was not paid for by any group, nor does it represent the views of any specific organisation. Sources can be provided upon request.]

Comments